“You can’t really understand what is going on now without understanding what came before.”

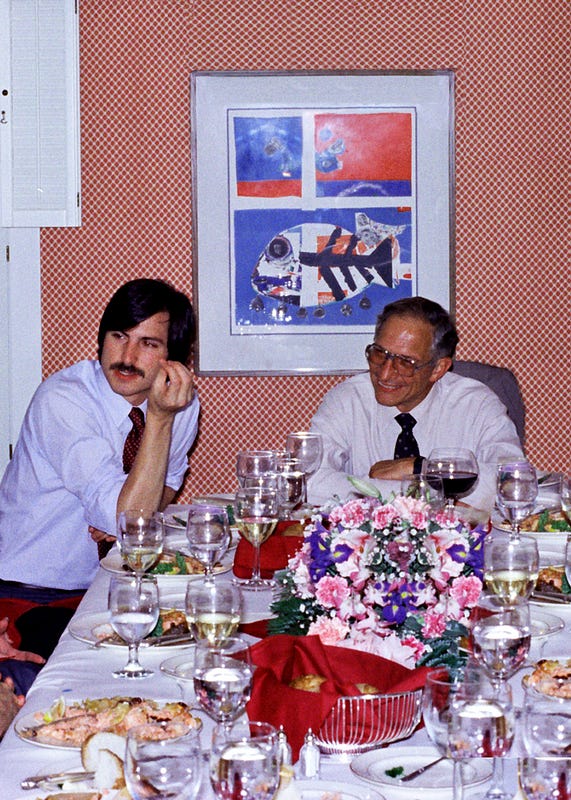

Steve Jobs is explaining why, as a young man, he spent so much time with the Silicon Valley entrepreneurs a generation older, men like Robert Noyce, Andy Grove, and Regis McKenna.

It’s a beautiful Saturday morning in May, 2003, and I’m sitting next to Jobs on his living room sofa, interviewing him for a book I’m writing. I ask him to tell me more about why he wanted, as he put it, “to smell that second wonderful era of the valley, the semiconductor companies leading into the computer.” Why, I want to know, is it not enough to stand on the shoulders of giants? Why does he want to pick their brains?

“It’s like that Schopenhauer quote about the conjurer,” he says. When I look blank, he tells me to wait and then dashes upstairs. He comes down a minute later holding a book and reading aloud:

He who lives to see two or three generations is like a man who sits some time in the conjurer’s booth at a fair, and witnesses the performance twice or thrice in succession. The tricks were meant to be seen only once, and when they are no longer a novelty and cease to deceive, their effect is gone.

History, Jobs understood, gave him a chance to see — and see through — the conjurer’s tricks before they happened to him, so he would know how to handle them.

Flash forward eleven years. It’s 2014, and I am going to see Robert W. Taylor. In 1966, Taylor convinced the Department of Defense to build the ARPANET that eventually formed the core of the Internet. He went on to run the famous Xerox PARC Computer Science Lab that developed the first modern personal computer. For a finishing touch, he led one of the teams at DEC behind the world’s first blazingly fast search engine — three years before Google was founded.

Visiting Taylor is like driving into a Silicon Valley time machine. You zip past the venture capital firms on Sand Hill Road, over the 280 freeway, and down a twisty two-lane street that is nearly impassable on weekends, thanks to the packs of lycra-clad cyclists on multi-thousand-dollar bikes raising their cardio thresholds along the steep climbs. A sharp turn and you enter what seems to be another world, wooded and cool, the coastal redwoods dense along the hills. Cell phone signals fade in and out in this part of Woodside, far above Buck’s Restaurant where power deals are negotiated over early-morning cups of coffee. GPS tries valiantly to ascertain a location — and then gives up.

When I get to Taylor’s home on a hill overlooking the Valley, he tells me about another visitor who recently took that drive, apparently driven by the same curiosity that Steve Jobs had: Mark Zuckerberg, along with some colleagues at the company he founded, Facebook.

“Zuckerberg must have heard about me in some historical sense,” Taylor recalls in his Texas drawl. “He wanted to see what I was all about, I guess.”

To invent the future, you must understand the past.

I am a historian, and my subject matter is Silicon Valley. So I’m not surprised that Jobs and Zuckerberg both understood that the Valley’s past matters today and that the lessons of history can take innovation further. When I talk to other founders and participants in the area, they also want to hear what happened before. Their questions usually boil down to two: Why did Silicon Valley happen in the first place, and why has it remained at the epicenter of the global tech economy for so long?

I think I can answer those questions.

First, a definition of terms. When I use the term “Silicon Valley,” I am referring quite specifically to the narrow stretch of the San Francisco Peninsula that is sandwiched between the bay to the east and the Coastal Range to the west. (Yes, Silicon Valley is a physical valley — there are hills on the far side of the bay.) Silicon Valley has traditionally comprised Santa Clara County and the southern tip of San Mateo County. In the past few years, parts of Alameda County and the city of San Francisco can also legitimately be considered satellites of Silicon Valley, or perhaps part of “Greater Silicon Valley.”

The name “Silicon Valley,” incidentally, was popularized in 1971 by a hard-drinking, story-chasing, gossip-mongering journalist named Don Hoefler, who wrote for a trade rag called Electronic News. Before, the region was called the “Valley of the Hearts Delight,” renowned for its apricot, plum, cherry and almond orchards.

“This was down-home farming, three generations of tranquility, beauty, health, and productivity based on family farms of small acreage but bountiful production,” reminisced Wallace Stegner, the famed Western writer. To see what the Valley looked like then, watch the first few minutes of this wonderful 1948 promotional video for the “Valley of the Heart’s Delight.”

Three historical forces — technical, cultural, and financial — created Silicon Valley.

Technology

On the technical side, in some sense the Valley got lucky. In 1955, one of the inventors of the transistor, William Shockley, moved back to Palo Alto, where he had spent some of his childhood. Shockley was also a brilliant physicist — he would share the Nobel Prize in 1956 — an outstanding teacher, and a terrible entrepreneur and boss. Because he was a brilliant scientist and inventor, Shockley was able to recruit some of the brightest young researchers in the country — Shockley called them “hot minds” — to come work for him 3,000 miles from the research-intensive businesses and laboratories that lined the Eastern Seaboard from Boston to Bell Labs in New Jersey. Because Shockley was an outstanding teacher, he got these young scientists, all but one of whom had never built transistors, to the point that they not only understood the tiny devices but began innovating in the field of semiconductor electronics on their own.

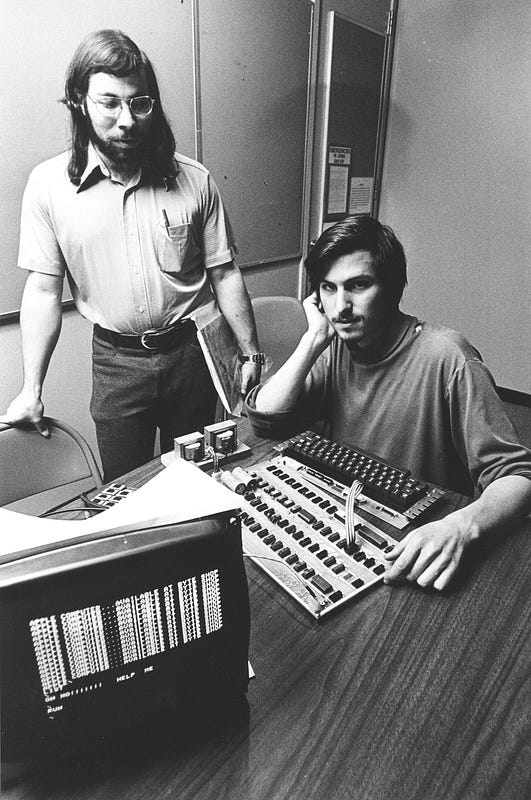

And because Shockley was a terrible boss — the sort of boss who posted salaries and subjected his employees to lie-detector tests — many who came to work for him could not wait to get away and work for someone else. That someone else, it turned out, would be themselves. The move by eight of Shockley’s employees to launch their own semiconductor operation called Fairchild Semiconductor in 1957 marked the first significant modern startup company in Silicon Valley. After Fairchild Semiconductor blew apart in the late-1960s, employees launched dozens of new companies (including Intel, National and AMD) that are collectively called the Fairchildren.

Equally important for the Valley’s future was the technology that Shockley taught his employees to build: the transistor. Nearly everything that we associate with the modern technology revolution and Silicon Valley can be traced back to the tiny, tiny transistor.

Think of the transistor as the grain of sand at the core of the Silicon Valley pearl. The next layer of the pearl appeared when people strung together transistors, along with other discrete electronic components like resistors and capacitors, to make an entire electronic circuit on a single slice of silicon. This new device was called a microchip. Then someone came up with a specialized microchip that could be programmed: the microprocessor. The first pocket calculators were built around these microprocessors. Then someone figured out that it was possible to combine a microprocessor with other components and a screen — that was a computer. People wrote code for those computers to serve as operating systems and software on top of those systems. At some point people began connecting these computers to each other: networking. Then people realized it should be possible to “virtualize” these computers and store their contents off-site in a “cloud,” and it was also possible to search across the information stored in multiple computers. Then the networked computer was shrunk — keeping the key components of screen, keyboard, and pointing device (today a finger) — to build tablets and palm-sized machines called smart phones. Then people began writing apps for those mobile devices … .

You get the picture. These changes all kept pace to the metronomic tick-tock of Moore’s Law.

The skills learned through building and commercializing one layer of the pearl underpinned and supported the development of the next layer or developments in related industries. Apple, for instance, is a company that people often speak of as sui generis, but Apple Computer’s early key employees had worked at Intel, Atari, or Hewlett-Packard. Apple’s venture capital backers had either backed Fairchild or Intel or worked there. The famous Macintosh, with its user-friendly aspect, graphical-user interface, overlapping windows, and mouse was inspired by a 1979 visit Steve Jobs and a group of engineers paid to XEROX PARC, located in the Stanford Research Park. In other words, Apple was the product of its Silicon Valley environment and technological roots.

Culture

This brings us to the second force behind the birth of Silicon Valley: culture. When Shockley, his transistor and his recruits arrived in 1955, the valley was still largely agricultural, and the small local industry had a distinctly high-tech (or as they would have said then, “space age”) focus. The largest employer was defense contractor Lockheed. IBM was about to open a small research facility. Hewlett-Packard, one of the few homegrown tech companies in Silicon Valley before the 1950s, was more than a decade old.

Stanford, meanwhile, was actively trying to build up its physics and engineering departments. Professor (and Provost from 1955 to 1965) Frederick Terman worried about a “brain drain” of Stanford graduates to the East Coast, where jobs were plentiful. So he worked with President J.E. Wallace Sterling to create what Terman called “a community of technical scholars” in which the links between industry and academia were fluid. This meant that as the new transistor-cum-microchip companies began to grow, technically knowledgeable engineers were already there.

These trends only accelerated as the population exploded. Between 1950 and 1970, the population of Santa Clara County tripled, from roughly 300,000 residents to more than 1 million. It was as if a new person moved into Santa Clara County every 15 minutes for 20 years. The newcomers were, overall, younger and better educated than the people already in the area. The Valley changed from a community of aging farmers with high school diplomas to one filled with 20-something PhDs.

All these new people pouring into what had been an agricultural region meant that it was possible to create a business environment around the needs of new companies coming up, rather than adapting an existing business culture to accommodate the new industries. In what would become a self-perpetuating cycle, everything from specialized law firms, recruiting operations and prototyping facilities; to liberal stock option plans; to zoning laws; to community college course offerings developed to support a tech-based business infrastructure.

Historian Richard White says that the modern American West was “born modern” because the population followed, rather than preceded, connections to national and international markets. Silicon Valley was bornpost-modern, with those connections not only in place but so taken for granted that people were comfortable experimenting with new types of business structures and approaches strikingly different from the traditional East Coast business practices with roots nearly two centuries old.

From the beginning, Silicon Valley entrepreneurs saw themselves in direct opposition to their East Coast counterparts. The westerners saw themselves as cowboys and pioneers, working on a “new frontier” where people dared greatly and failure was not shameful but just the quickest way to learn a hard lesson. In the 1970s, with the influence of the counterculture’s epicenter at the corner of Haight and Ashbury, only an easy drive up the freeway, Silicon Valley companies also became famous for their laid-back, dressed-down culture, and for their products, such as video games and personal computers, that brought advanced technology to “the rest of us.”

Money

The third key component driving the birth of Silicon Valley, along with the right technology seed falling into a particularly rich and receptive cultural soil, was money. Again, timing was crucial. Silicon Valley was kick-started by federal dollars. Whether it was the Department of Defense buying 100% of the earliest microchips, Hewlett-Packard and Lockheed selling products to military customers, or federal research money pouring into Stanford, Silicon Valley was the beneficiary of Cold War fears that translated to the Department of Defense being willing to spend almost anything on advanced electronics and electronic systems. The government, in effect, served as the Valley’s first venture capitalist.

The first significant wave of venture capital firms hit Silicon Valley in the 1970s. Both Sequoia Capital and Kleiner Perkins Caufield and Byers were founded by Fairchild alumni in 1972. Between them, these venture firms would go on to fund Amazon, Apple, Cisco, Dropbox, Electronic Arts, Facebook, Genentech, Google, Instagram, Intuit, and LinkedIn — and that is just the first half of the alphabet.

This model of one generation succeeding and then turning around to offer the next generation of entrepreneurs financial support and managerial expertise is one of the most important and under-recognized secrets to Silicon Valley’s ongoing success. Robert Noyce called it “re-stocking the stream I fished from.” Steve Jobs, in his remarkable 2005 commencement address at Stanford, used the analogy of a baton being passed from one runner to another in an ongoing relay across time.

So that’s how Silicon Valley emerged. Why it has it endured?

After all, if modern Silicon Valley was born in the 1950s, the region is now in its seventh decade. For roughly two-thirds of that time, Valley watchers have predicted its imminent demise, usually with an allusion to Detroit. First, the oil shocks and energy crises of the 1970s were going to shut down the fabs (specialized factories) that build microchips. In the 1980s, Japanese competition was the concern. The bursting of the dot-com bubble, the rise of formidable tech regions in other parts of the world, the Internet and mobile technologies that make it possible to work from anywhere: all have been heard as Silicon Valley’s death knell.

The Valley economy is notorious for its cyclicity, but it has indeed endured. Here we are in 2015, a year in which more patents, more IPOs, and a larger share of venture capital and angel investments have come from the Valley than ever before. As arecent report from Joint Venture Silicon Valley put it, “We’ve extended a four-year streak of job growth, we are among the highest income regions in the country, and we have the biggest share of the nation’s high-growth, high-wage sectors.” Would-be entrepreneurs continue to move to the Valley from all over the world. Even companies that are not started in Silicon Valley move there (witness Facebook).

Why? What is behind Silicon Valley’s staying power? The answer is that many of the factors that launched Silicon Valley in the 1950s continue to underpin its strength today even as the Valley economy has proven quite adaptable.

Technology

The Valley still glides in the long wake of the transistor, both in terms of technology and in terms of the infrastructure to support companies that rely on semiconductor technology. Remember the pearl. At the same time, when new industries not related directly to semiconductors have sprung up in the Valley — industries like biotechnology — they have taken advantage of the infrastructure and support structure already in place.

Money

Venture capital has remained the dominant source of funding for young companies in Silicon Valley. In 2014, some $14.5 billion in venture capital was invested in the Valley, accounting for 43 percent of all venture capital investments in the country. More than half of Silicon Valley venture capital went to software investments, and the rise of software, too, helps to explain the recent migration of many tech companies to San Francisco. (San Francisco, it should be noted, accounted for nearly half of the $14.5 billion figure.) Building microchips or computers or specialized production equipment — things that used to happen in Silicon Valley — requires many people, huge fabrication operations and access to specialized chemicals and treatment facilities, often on large swaths of land. Building software requires none of these things; in fact, software engineers need little more than a computer and some server space in the cloud to do their jobs. It is thus easy for software companies to locate in cities like San Francisco, where many young techies want to live.

Culture

The Valley continues to be a magnet for young, educated people. The flood of intranational immigrants to Silicon Valley from other parts of the country in the second half of the twentieth century has become, in the twenty-first century, a flood of international immigrants from all over the world. It is impossible to overstate the importance of immigrants to the region and to the modern tech industry. Nearly 37 percent of the people in Silicon Valley today were born outside of the United States — of these, more than 60 percent were born in Asia and 20 percent in Mexico. Half of Silicon Valley households speak a language other than English in the home. Sixty-five percent of the people with Bachelors degrees working in the valley were born in another country. Let me say that again: 2/3 of people in the Valley who have completed their college education are foreign born.

Here’s another way to look at it: From 1995 to 2005, more than half of all Silicon Valley startups had at least one founder who was born outside the United States.[13] Their businesses — companies like Google and eBay — have created American jobs and billions of dollars in American market capitalization.

Silicon Valley, now, as in the past, is built and sustained by immigrants.

Stanford also remains at the center of the action. By one estimate, from 2012, companies formed by Stanford entrepreneurs generate world revenues of $2.7 trillion annually and have created 5.4 million jobs since the 1930s. This figure includes companies whose primary business is not tech: companies like Nike, Gap, and Trader Joe’s. But even if you just look at Silicon Valley companies that came out of Stanford, the list is impressive, including Cisco, Google, HP, IDEO, Instagram, MIPS, Netscape, NVIDIA, Silicon Graphics, Snapchat, Sun, Varian, VMware, and Yahoo. Indeed, some critics have complained that Stanford has become overly focused on student entrepreneurship in recent years — an allegation that I disagree with but is neatly encapsulated in a 2012 New Yorker article that called the university“Get Rich U.”

Change

The above represent important continuities, but change has also been vital to the region’s longevity. Silicon Valley has been re-inventing itself for decades, a trend that is evident with a quick look at the emerging or leading technologies in the area:

• 1940s: instrumentation

• 1950s/60s: microchips

• 1970s: biotech, consumer electronics using chips (PC, video game, etc)

• 1980s: software, networking

• 1990s: web, search

• 2000s: cloud, mobile, social networking

The overriding sense of what it means to be in Silicon Valley — the lionization of risk-taking, the David-versus-Goliath stories, the persistent belief that failure teaches important business lessons even when the data show otherwise — has not changed, but over the past few years, a new trope has appeared alongside the Western metaphors of Gold Rushes and Wild Wests: Disruption.

“Disruption” is the notion, roughly based on ideas first proposed by Joseph Schumpeter in 1942, that a little company can come in and — usually with technology — completely remake an industry that seemed established and largely impervious to change. So: Uber is disrupting the taxi industry. Airbnb is disrupting the hotel industry. The disruption story is, in its essentials, the same as the Western tale: a new approach comes out of nowhere to change the establishment world for the better. You can hear the same themes of adventure, anti-establishment thinking, opportunity and risk-taking. It’s the same song, with different lyrics.

The shift to the new language may reflect the key role that immigrants play in today’s Silicon Valley. Many educated, working adults in the region arrived with no cultural background that promoted cowboys or pioneers. These immigrants did not even travel west to get to Silicon Valley. They came east, or north. It will be interesting to see how long the Western metaphor survives this cultural shift. I’m betting that it’s on its way out.

Something else new has been happening in Silicon Valley culture in the past decade. The anti-establishment little guys have become the establishment big guys. Apple settled an anti-trust case. You are hearing about Silicon Valley companies like Facebook or Google collecting massive amounts of data on American citizens, some of which has ended up in the hands of the NSA. What happens when Silicon Valley companies start looking like the Big Brother from the famous 1984 Apple Macintosh commercial?

A Brief Feint at the Future

I opened these musings by defining Silicon Valley as a physical location. I’m often asked how or whether place will continue to matter in the age of mobile technologies, the Internet and connections that will only get faster. In other words, is region an outdated concept?

I believe that physical location will continue to be relevant when it comes to technological innovation. Proximity matters. Creativity cannot be scheduled for the particular half-hour block of time that everyone has free to teleconference. Important work can be done remotely, but the kinds of conversations that lead to real breakthroughs often happen serendipitously. People run into each other down the hall, or in a coffee shop, or at a religious service, or at the gym, or on the sidelines of a kid’s soccer game.

It is precisely because place will continue to matter that the biggest threats to Silicon Valley’s future have local and national parameters. Silicon Valley’s innovation economy depends on its being able to attract the brightest minds in the world; they act as a constant innovation “refresh” button. If Silicon Valley loses its allure for those people — if the quality of public schools declines so that their children cannot receive good educations, if housing prices remain so astronomical that fewer than half of first-time buyers can afford the median-priced home, or if immigration policy makes it difficult for high-skilled immigrants who want to stay here to do so — the Valley’s status, and that of the United States economy, will be threatened. Also worrisome: ever-expanding gaps between the highest and lowest earners in Silicon Valley; stagnant wages for low- and middle-skilled workers; and the persistent reality that as a group, men in Silicon Valley earn more than women at the same level of educational attainment. Moreover, today in Silicon Valley, the lowest-earning racial/ethnic group earns 70 percent less than the highest earning group, according to the Joint Venture report. The stark reality, with apologies to George Orwell, is that even in the Valley’s vaunted egalitarian culture, some people are more equal than others.

Another threat is the continuing decline in federal support for basic research. Venture capital is important for developing products into companies, but the federal government still funds the great majority of basic research in this country. Silicon Valley is highly dependent on that basic research — “No Basic Research, No iPhone” is my favorite title from a recently released report on research and development in the United States. Today, the US occupies tenth place among OECD nations in overall R&D investment. That is investment as a percentage of GDP — somewhere between 2.5 and 3 percent. This represents a 13 percent drop below where we were ten years ago (again as a percentage of GDP). China is projected to outspend the United States in R&D within the next ten years, both in absolute terms and as a fraction of economic development.

People around the world have tried to reproduce Silicon Valley. No one has succeeded.

And no one will succeed because no place else — including Silicon Valley itself in its 2015 incarnation — could ever reproduce the unique concoction of academic research, technology, countercultural ideals and a California-specific type of Gold Rush reputation that attracts people with a high tolerance for risk and very little to lose. Partially through the passage of time, partially through deliberate effort by some entrepreneurs who tried to “give back” and others who tried to make a buck, this culture has become self-perpetuating.

The drive to build another Silicon Valley may be doomed to fail, but that is not necessarily bad news for regional planners elsewhere. The high-tech economy is not a zero-sum game. The twenty-first century global technology economy is large and complex enough for multiple regions to thrive for decades to come — including Silicon Valley, if the threats it faces are taken seriously.

Leslie Berlin is Project Historian for the Silicon Valley Archives at Stanford University, and author of The Man Behind the Microchip: Robert Noyce and the Invention of Silicon Valley.

No comments:

Post a Comment